This article was originally published by Abode Magazine and describes VMDO's “three studios, one firm” structure and what's on the boards for the firm.

Since it began in 1976, VMDO—the firm that won Best Architect in this year’s Best of C-VILLE reader poll—has come a long way. And it’s established itself as a part of Charlottesville, both as a physical presence at its downtown office—housed in a onetime YMCA facility—and as the design force behind many local landmarks, including (full circle alert!) the brand-new Brooks Family YMCA.

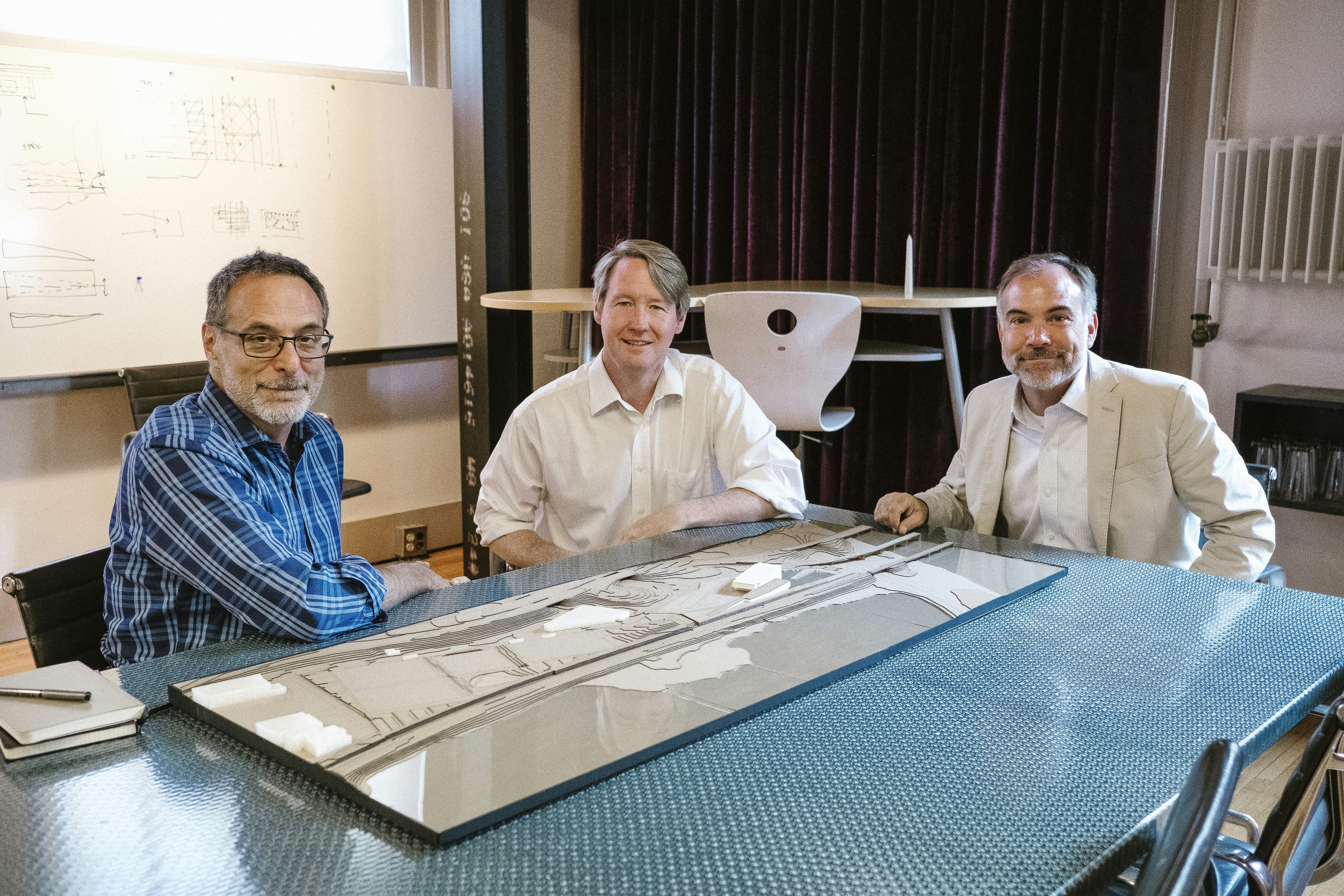

I sat down with three of the firm’s principals—Joe Atkins, Joe Celentano and Wyck Knox—to talk about its “three studios, one firm” structure and learn what’s currently on the VMDO boards. It was clear that in this day and age, institutional architecture involves vastly more than floor plans; it’s an opportunity to contribute to planetary well-being, physical fitness for students and teachers and the nuts and bolts of education itself.

VMDO has garnered a number of awards for its educational and community projects, and has produced record-setting work—like Discovery Elementary School in Arlington, the largest zero-energy school in the country.

As the firm keeps growing, Celentano says, they face questions about whether they’ll need to expand geographically beyond the mid-Atlantic. But, he says, “We can’t imagine we would leave this spot. It’s so much a part of our identity.”

ABODE: How did the “three studios, one firm” approach come about?

Joe Atkins: When the firm grew to 50 or 60 people, in 2012, we looked at having three studios of 18 or so, to extend the joys of a small office. It was a chance to lightly specialize. [The studios focus on] higher education, K-12 and athletics and community. This was a natural way to focus for the outside world. Inside, we’re one firm.

Joe Celentano: Part of the reason for creating the specialization was marketing—competing against national firms who have quite a bit of specialization. Buildings are getting more complicated; having everybody be generalists was not a good strategy. We wanted to allow people to focus and dig in.

JA: Specializing has helped us advance some of the design to higher and higher levels.

Wyck Knox: We have a project that has been complete for two years with the Arlington, Virginia, public schools. They came to us because of another project in Manassas Park, where we redid the entire school system, and the last one won an AIA award. Being able to put stuff out there that’s recognized on a national level opens the door for other projects. We are just in one location, a regional firm in the mid-Atlantic. Elevating the work and getting attention at a national level is essential.

What are some of the new design challenges you face these days?

WK: We’re seeing a lot more push into health and wellness. Our role includes researching and specifying transparent materials. It’s surprisingly hard—finding chemicals of concern and getting them out of building products. That’s a whole new wave, basically putting food labels on products. Architects are in a good position to move the market.

JC: There’s a movement toward evidence-based design. People want to see the results of the strategies. Clients are interested in how you can equate these things to test scores.

WK: There are Physical Activity Design Guidelines [partly growing out of Michelle Obama’s initiatives on childhood obesity]. Essentially, you have multistory buildings and design beautiful, compelling stairs that people want to take. You tuck the elevator around the corner. And as development continues and there’s less and less available land, we can’t sprawl like we used to anyway. Then there are Healthy Eating Design Guidelines. The order in which you present food is important—put the fruit and vegetables first. So is the idea of choice; if you give celery and carrots, overall vegetable consumption goes up compared to if you offer just carrots. The idea of diversity and choice has carried on to furnishings. A classroom shouldn’t have 26 identical chairs.

A lot of buildings have used a dashboard where a touchscreen displays energy and water use information. They have been somewhat successful, but we wanted to design one from scratch. We used 360-degree photos of the building so that you can “enter” a room, click on a light and find out how much power it uses. There are a lot of teachable moments.

JC: The things we’re talking about were not part of our practice 10 or 20 years ago.

Can you tell us about current projects in your respective studios?

JA: In the Higher Education studio, we’re designing the Liberty University School of Music and Concert Hall. It’s a pioneering venue in the way that it is finely tuned for natural (unamplified) acoustics, but has first-of-its-kind flexibility for digital acoustics. The room itself can become part of the piece.

WK: In K-12, energy-efficient design has become second nature for us, and we have three projects that we expect will be in the 10 or 20 most energy-efficient schools in the country. We’re just starting a project in Lancaster County, Virginia, a small school system. They need to rebuild all their schools, and they’re thinking about things as radical as “Let’s eliminate grades.” You never know where you’ll find those clients. We understand people that want to do things a little differently.

JC: I’m with the Athletics and Community studio. At UVA, we’re partnered with the Aidlin Darling firm from San Francisco to design the Contemplative Sciences Center at UVA. There’s more interest now in how contemplative practice, like meditation and yoga, affects learning. It’ll be a place for practice, learning and research; the university is going to be at the forefront of this. It’s located in a fantastic spot next to the Dell, and it has this opportunity to make a connection between the building and nature.

We’re also working on the Arlington Community Center. Arlington County has a mix of urban and suburban conditions. They’re taking a proactive approach, and the community is very engaged in the process and concerned about preserving open space. The site has a natural area and a little stream. Our approach is to integrate the building with the park; a good part of the building is underground. Above, it’s more like a pavilion. It’s an interesting public process; everybody has a voice, but nobody can dominate. It becomes a collective voice.

WK: We’ve developed a sub-expertise in community engagement. The moment of success is the pronoun flip, when community members change from saying, “What are they going to do?” to “What are we going to do?”