“Resilience is the ability to face internal or external crisis and not only effectively resolve it, but also learn from it, be strengthened by it, emerge transformed by it, individually and as a group.” --Gilbert Brenson-Lazan

Grappling with COVID-19 and its many disruptions to our society and economy has inspired us to reach out to people with insight to share. From addressing the challenges of distance learning to re-examining the relationship between public space and public health, our clients, colleagues, and collaborators share reflections on this moment, what they’re learning, and how they think design can be a partner in enabling future solutions. If our future is changing, we must as well.

Let’s design it together.

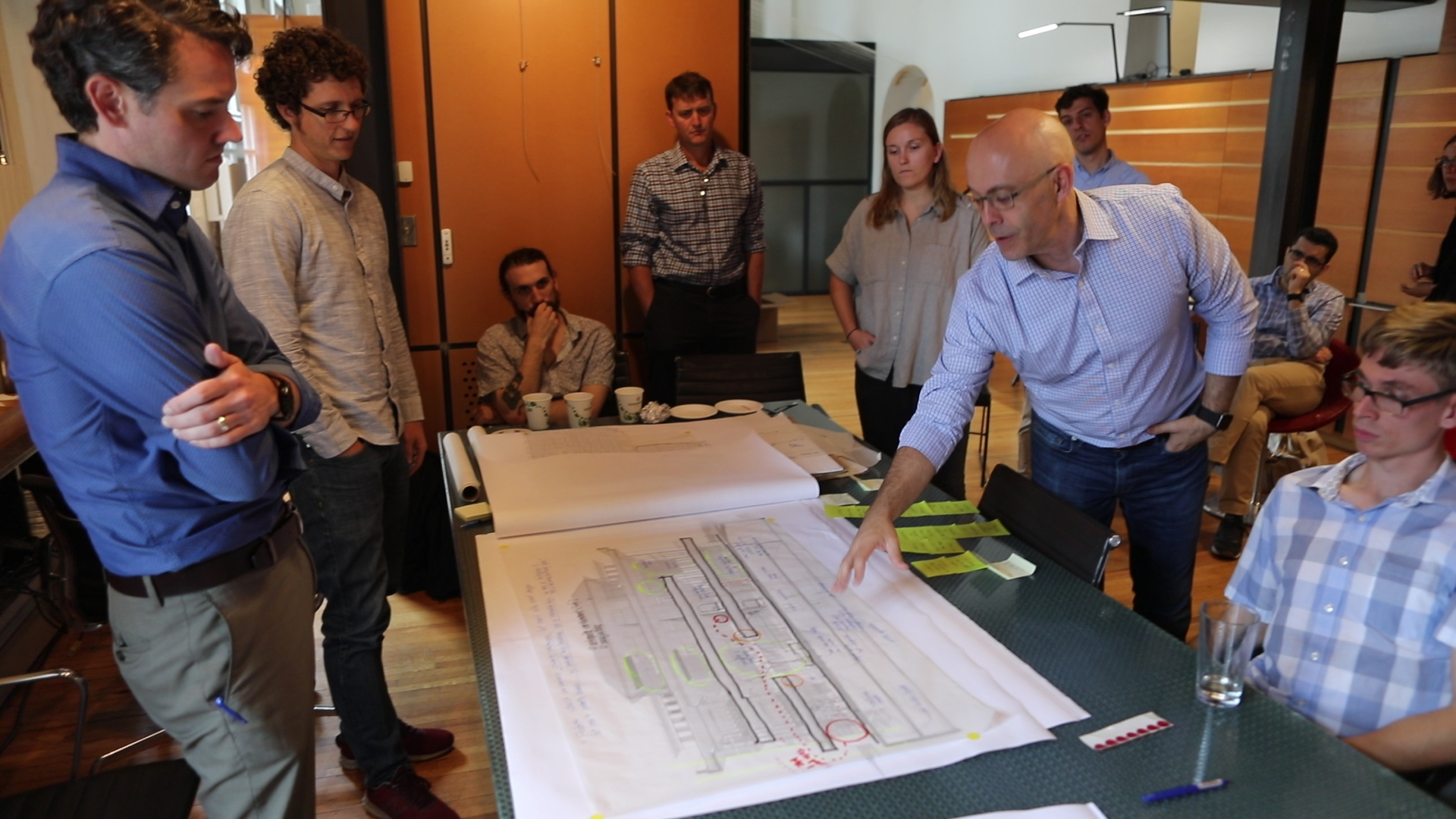

Dr. Trowbridge reviews designs of UVA's Student Health + Wellness Center during a design-thinking charrette with VMDO.

Dr. Trowbridge reviews designs of UVA's Student Health + Wellness Center during a design-thinking charrette with VMDO.

Dr. Matthew Trowbridge is a physician, public health researcher, and associate professor at the University of Virginia School of Medicine. Dr. Trowbridge’s academic research focuses on the impact of architecture, urban design, and transportation planning on public health. He currently leads the Green Health Partnership between UVA and the U.S. Green Building Council with funding from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. The partnership is focused on leveraging green building market transformation tools to promote public health.

He is also the director and co-founder of the UVA Medical Design Program and recently contributed a chapter in the new book Health Design Thinking (MIT Press 2020) by Dr. Bon Ku and Ellen Lupton, which makes this case for applying the principles of design thinking to real-world health care challenges.

Previously, Dr. Trowbridge has been a senior advisor to the National Collaborative on Childhood Obesity Research. Along with VMDO and public health researchers, Dr. Trowbridge contributed to the Healthy Eating Design Guidelines for School Architecture (CDC 2012) and the Physical Activity Design Guidelines for School Architecture (PLOS ONE 2015), research that informed VMDO’s health-focused approach to designing the Buckingham School in Dillwyn, Virginia.

Transcript:

Q1: Lauren Shirley

All of our day to day lives have changed since the pandemic began, even if the work we do has stayed the same. Given your involvement with the UVA Hospital, in what ways has your work changed since the pandemic began?

A1: Dr. Matthew Trowbridge

One of the most radical things that occurred was that all of our students had to leave clinical rotations and go home. Like educators across the country and across domains, we had to figure out in a matter of a week how to make medical school virtual which has been incredibly challenging and very stressful. It's especially stressful for our medical students, particularly third years, who have waited for this exact moment to be finally transitioning into their clinical rotations and getting into the hospital and taking care of real patients.

It's been a very challenging time. We've had to figure out how to bring as much of that clinical experience to our students and also satisfy very real things like making sure they're getting enough credits for graduation and all these sorts of things. The honest truth is we're still figuring this out. I think there's a lot of work going on to figure out, well, how can you bring as much of the virtual clinical care component to students as possible. It's a work in progress.

Q2: Lauren Shirley

Much of your writing, research, teaching and passion about public health focuses on the impact design can have on health outcomes. How has COVID-19 shifted your thinking about the connection between public space and public health?

A2: Dr. Matthew Trowbridge

COVID-19 hasn't really shifted my thinking about the importance of public space and public health. I think it's just brought it into very clear relief. Here in Charlottesville public spaces have always been popular. Now they're essential, and I think they're seen as essential by a lot of people.

I think people are realizing what it means to be in public space. We take it for granted. And now I think you appreciate open areas that are accessible to your home, opportunities for safe exercise, and opportunities to be walkable to things. I think public space is suddenly on everyone's mind. That's something we, who think about the built environment, have known for a long time. I just think it's more in the public eye, is really the way I would say it.

Lauren Shirley

I think it goes beyond our access to natural areas. I think it also involves protocols around shared, public spaces like the post office or anything related to our civic functions. I would consider a grocery store public space. The way we behave in those spaces and the way they're set up is also coming into sharper resolution.

Dr. Matthew Trowbridge

Absolutely, everywhere is suddenly a public space. Whether you're inside a building or out. I think it's a stressful time in that every single organization and every building owner is suddenly faced with this complex thing. Customers are suddenly thinking about, “Hey, how well are you managing your facility, and how was it designed, and how well are you adapting to use it in this new way during COVID-19?”

Q3: Lauren Shirley

As a designer, I feel like the amount of research that's available that directly links building strategies with health outcomes is fairly sparse. How does this moment offer new opportunities for conducting research and capturing data for the future?

A3: Dr. Matthew Trowbridge

I think what you really need is interest in participation, and I think that is what COVID-19 is really generating. I think there's a huge interest right now in transparency among building occupants. They want to know more about buildings and the policies in place.

I think that's been something that we've always wanted for things like sustainability – i.e. how do you build engagement with a building if you've built-in an amazing HVAC system, or lighting system, to make sure it's being used appropriately? I think it's going be the same way for health, and I think COVID-19 will make people want to know more and be more actively involved.

If everyone in a group knows that they're coming back to work, but perhaps before a vaccine is available, then we're all going to need to be able to trust each other – to trust the building and trust the policies that are in place. Engagement is possible in a brand-new way because we all suddenly have been forced into realizing and taking stock of “what is the environment I live in? How does it impact how I interact with people?”

There's an amazing story here about empathy – i.e. realizing what it must be like to walk around as a patient who is immunocompromised on a daily basis. We're all experiencing that [feeling]. The sense that, “Hey, I need some more physical space right now.” Or, “I need something out of the environment. Which environments provide that for me? And give me that flexibility to get what I need while also still trying to maintain a social connection?”

I think the fact that we've all had that shared experience – that's going to drive engagement going forward. And I think it's up to us, as thought leaders in this space, to take advantage of that and encourage that – particularly once this pandemic subsides.

Q4: Lauren Shirley

You have compellingly argued that buildings aren’t inert. They can either help or hurt. The issue on everybody’s mind right now is how do we reopen and how do we go back to work?

A4: Dr. Matthew Trowbridge

I know there won't be a perfect checklist for ensuring safe reopening of any building or organization. I think instead you can make a commitment to being transparent about a systematic process that you're going to follow. Make those features and policies transparent to the people who are going to be using your building. I think that's going to be the mark of a high performance organization.

We're going to have to work through being in an environment that we're not used to being in. I think one where you really cannot assure 100% safety just from the building alone. Ultimately, it's going to be about having a kind of shared trust and a kind of mutual agreement – a mutual engagement, as we've been talking about – among the people who are going to use a building together. That we can trust each other. That we can abide by a set of guidelines. And that we are going to invest in things that will be forthcoming, like much more universal testing and engagement with systems like contact tracing.

That's what we're going to need. But, you're going to have to keep changing and evaluating your process periodically as the available technologies and available health options change – because they will change. This won't be done in a week, but I am optimistic that we're going to find ways to get back into resuming some of the core functions of our society. It won't be the same thing as it was before. It's going to be something new.