Engaging Communities in Public Library Design

What kind of library do you want to be?

This is the first question we ask our clients when we begin a new library design project. We start here because we know from experience the breadth of possible responses. We have recently partnered with library clients to design new civic amenities that are combinations of community gathering spaces, living rooms, learning gardens, tech hubs, information stations, and centers for wellbeing. What we hear from our clients about their needs, ideas, and hopes for their institutions defies the conventional use of the word library. But even more importantly, we start here because we intend to create a design in response to the community, not impose our vision of a 21st century library onto them.

Over the past few years, VMDO has engaged with public library projects ranging in size, budget, location, and demographics served. We have worked with libraries in Florida, Virginia, and New York to revitalize their facilities and expand the notion of a what a library can be to their communities. This work has given us opportunities to hone our community engagement methods and develop strategies and tools specific to library design.

Our Approach

Our first principle for community engagement is that we listen well. We come into each conversation with a beginner’s mindset, knowing that although we have design expertise, the library leadership, staff, and community members are experts of their own experience. They can offer insights on a range of relevant topics, from the history and culture of the community to the way their current facilities are used to unmet needs in the population served.

We believe that everyone has something to offer to the process, and this belief guides us to engage with representatives from each key stakeholder group. Our work in the early stages of the project involves forging as many connections as we can to encourage participation from people of different ages, background, and abilities. Our goal with each engagement opportunity is to gather groups that truly represent the community.

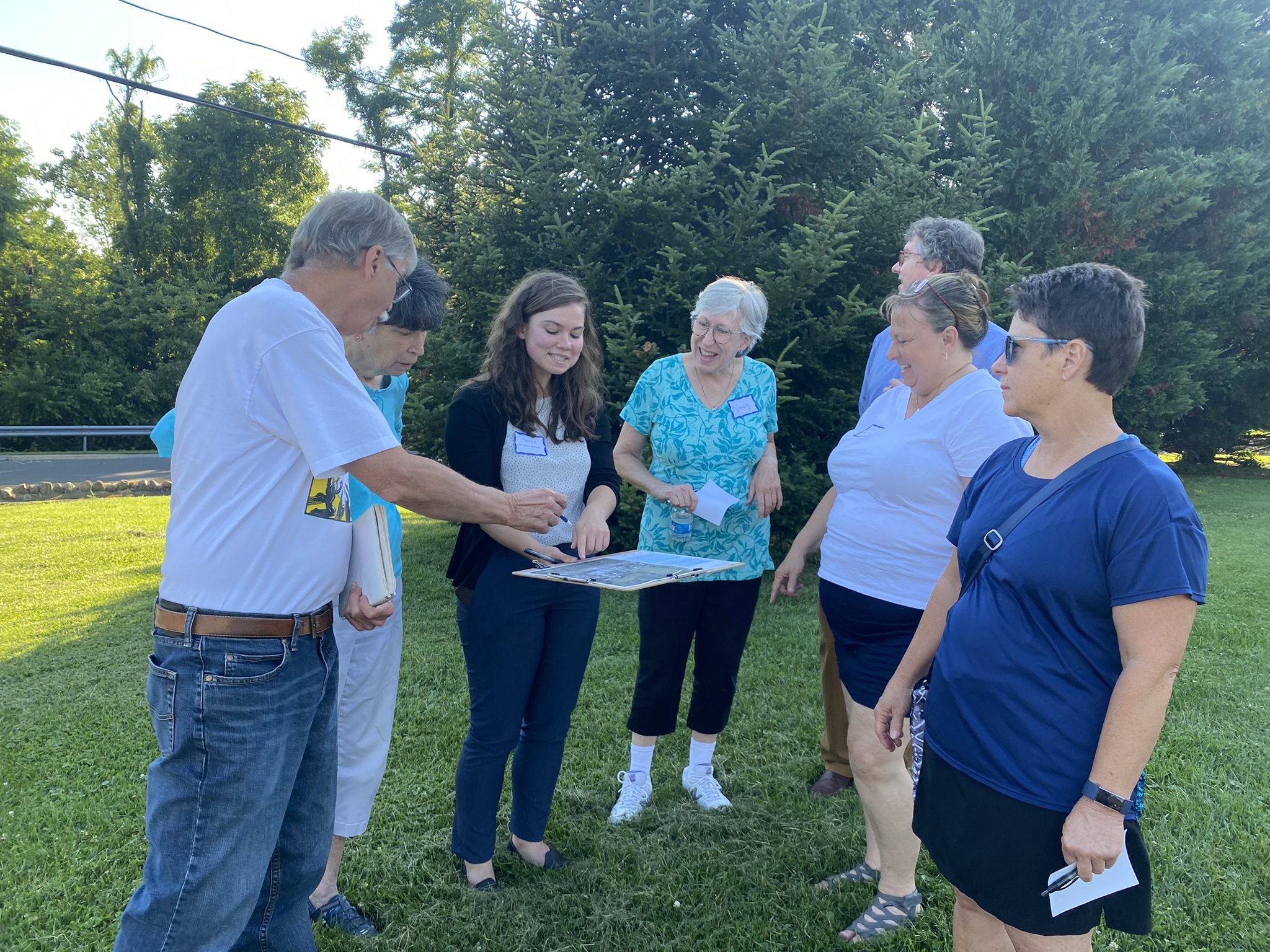

To create a workshop setting that fosters meaningful collaboration, we tailor the engagement experience to the context and the participants. There is no standard methodology that works for every project; each opportunity demands an intentional approach with customized strategies and engagement tools. For example, in our recent collaboration with Shenandoah County, our preliminary analysis of the site conditions revealed the potential to redevelopment the site and create memorable outdoor spaces. In the engagement sessions that followed, we walked the site with library staff and community members to hear how the landscape design could enhance the library’s programs and services.

Common Challenges

Practicing community engagement is not without its challenges. It requires following our client’s lead, building relationships, and earning the trust of the community. Working in this way requires a significant investment of time and resources. When we make community engagement a priority, we can only move “at the speed of trust,” and this requires a certain level of flexibility in the project schedule and deliverables. We have the experience-based expertise to design a realistic project schedule with sufficient time allocated for engagement, but because every community is different, we must continually adapt our approach. If something isn’t working, then we try another tactic. There are many ways to communicate, invite participation and encourage dialogue while keeping the core questions central to the engagement process.

When we design a community engagement process we are often faced with challenging questions about equity – about whether we are successfully reaching people from all walks of life and levels of comfort with the design process. We recognize that many people have barriers to participation – time and transportation among them – so we are always looking for ways to diversify our engagement methods and provide options to participate in person, on paper and online.

Lessons Learned

Our work has yielded meaningful lessons about the importance of partnerships and the value of being physically present for collaborations. In places where we have forged connections with community organizations, we have been able to attend their events and have more organic interactions in places where people are already gathering. We try to explore every potential avenue for collaboration, but we find success more consistently when we can meet people in person.

In our recent work with the UVA Law Library, we found this to be true with younger people, a population often stereotyped as preferring digital interactions. For this engagement, we set up a “storefront” experience where we positioned ourselves near the entry of the library with a survey displayed on digital monitors and a bowl of chocolate to entice participation. We observed a consistent pattern with the students who stopped to take the survey. They would begin the survey on the monitors, but eventually they would turn to us to talk about the questions. In this case the survey proved an effective way into building relationships. By providing students with the option to participate anonymously and making ourselves available to those who chose to engage, we were able to elicit active participation in conversations about the library and hear directly from one of the key constituent groups that the library exists to serve.

Rewards of Sustained Investment

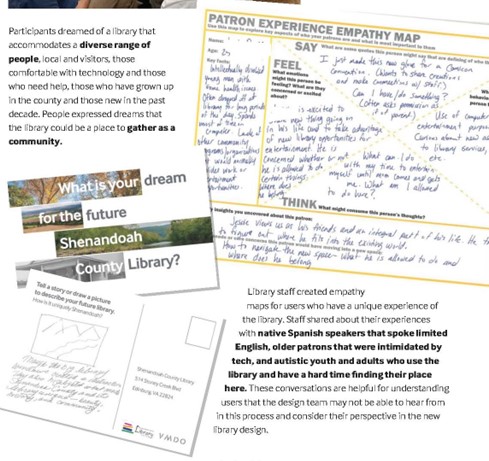

Our recent work with the Shenandoah County Library showed the power of investing time and resources in shaping a meaningful community engagement process. With a clear directive and shared commitment from our client, we allocated two months at the outset of the project to intensive engagement work. This began with a kickoff meeting where we worked with key project stakeholders to confirm the project schedule and budget goals, establish the overall objectives, and shape an initial vision for the future of the library. We then worked as a design team to craft an engagement process that involved writing custom surveys, organizing events and workshops, and producing materials tailored to these engagements.

Over the next two months we invited participation in several ways, through surveys we distributed online and in-person, through interviews and programming workshops with staff, and through visioning sessions with community members. We spent significant time on site, in face-to-face conversations, hands-on activities and site walks. We listened closely to the staff to understand who they are, how they work, and how they serve their community through the library. We experienced firsthand how much knowledge the librarians hold about their community and how well they understand what their patrons need and want in a library. Our conversations with community members ranged from the history and culture of Shenandoah County to their love for the natural beauty of the landscape, to how changing needs and expectations are reshaping the role of the library in the community.

Through these engagements we built relationships and cultivated investment from the staff and community members. By the last public meeting of the pre-design phase, when we presented the engagement outcomes, participation had increased ten-fold. Word had spread through the county and people were bringing friends and neighbors to join in on the project. These results make us optimistic that our design will respond well to its people and place, and that the people will become good stewards of the place because they helped to create it.

Building Learning Communities

Our approach to community engagement grows authentically from VMDO’s culture. We are a teaching firm that encourages our employees, clients, and students to question and (re)define the role of architecture in society – and become creative participants in future solutions. For nearly forty years we have focused our efforts on creating?places?of?learning, from K12 schools to universities, public institutions, and community nonprofit organizations. We believe these places should be expressive of a community’s highest ideals and represent those aims tangibly through environmentally sensitive designs that befit a community’s context, enduring traditions, and goals for future generations.

We know from experience that the most successful projects are the ones that evolve from genuine partnerships with our clients – from taking the approach of designing with and not for the people we serve and structuring processes that allow many voices to be heard and empowered. As we continue partnering with our library clients, we are looking forward to discovering new ways to engage and bring more people into the process of reimagining what a modern library can be.